This, surely, is a phrase that bounces across Exeter and beyond from one Exeter Cathedral School family to another every evening. I wonder, too, how many children respond with an enthusiastic “Yes! I was desperate to do it as soon as I came in from school!”. Some, but not many, I suspect.

This week, 217 music lessons have taken place here in school, a figure that shows that pupils here at Exeter Cathedral School are keen to learn instruments, perhaps with the intention of joining one of the many ensembles on offer both inside and outside of school, or to have fun making music at home. We really are fortunate to be able to offer a wide variety of instruments, and the pupils are taught by highly professional and skilled ‘Visiting Music Teachers’ who impart a wealth of knowledge during their half-hour lesson each week.

Through our regular Performers’ Platforms we witness first-hand our pupils’ progress on their instruments. We take delight in encouraging those (sometimes daunted) little faces perform a simple melody like ‘Ode to Joy’ as a beginner, and before you know it, they’ve turned into poised, confident Year 8 pupil performing a movement from a sonata by Mozart. Of course, this – the progress – can’t be achieved without practice. Like with any skill in life (take juggling for instance – I’ve always secretly wished I could do this), achieving proficiency takes hard graft. Malcom Gladwell famously stated that it takes 10,000 hours of practice to become a master of a skill, so if we relate this to music practice, it amounts to a lot of practice.*

I would, though, challenge the basic premise that it is all about the number of hours, (as I am sure many have done before me). It’s what you do with those hours that really make the difference. If your child spends 20 minutes practising their instrument but the time spent isn’t profitable then the progress will be fairly slow, ultimately, and the child will drift from one lesson to another, going over the same parts of the piece that had probably been worked on the week before.

The main objective in learning an instrument, surely, is to learn repertoire and take joy from playing. Right from the start, once two or three notes are learned on an instrument, a melody can be played. The melodies then become longer, and eventually turn into pieces which then might be played in an examination. The goal, when learning a new piece, is to be able to play it ‘fluently’, with few ‘slip ups’ and hardly any ‘moments of hesitation’ (language used in ABRSM marksheets across the board). Getting to this point, however, is hard work, takes time and yes, practice. Proper practice. “Easy for you to say!” I hear you bellowing at me. It’s true – I know what is meant by ‘proper practice’ and I can be of help (mostly not wanted) to my own children, but so often I hear parents who perhaps have not learned an instrument say that they “can’t be of any help” to their child. This is not the case: regardless of musical ability, if as parents you know the strategy your child should use to practice then this is a huge step in the right direction, and it needn’t take up much time each night. Here’s how:

How often have we heard our children play through a piece a couple of times, with stumbles and pauses, only for them to hop down from the piano stool, declare that they’ve done their music practice for the evening and insist that it’s their free time now? How many times have we also heard music practice start each time at the very beginning of the piece, which is usually quite good, only for the wheels to come off half way through? If this is happening, it’s likely that your child does not actually know how to get the best out of their practice, so here’s what you can tell them to remember and it’s fairly simple, a phrase I have coined just this week: The Three Rs – ‘Remove, Repair, Replace’.

Remove

‘Remove’: identify and isolate one, two, or maybe three bars of a piece of music that are causing difficulty and ask your child to mentally ‘remove’ them from the piece so that they only practise that bit. There will be reasons why it’s tricky; it could be because pianist has to shift hand position, or a violinist has to cross a string; whatever is causing the break in fluency, remove it so it can be fixed.

Repair

‘Repair’: practise these bars repeatedly, so that they’re fluent and so the issue is ‘repaired’. So much of what is played is done through muscle-memory, so by repeating it this will help the hands or voice remember what to do. It might be that in removing the passage and practising it your child discovers that it’s only a few notes that are the issues. In which case, practise just these, over and over again, slowly, fast, and even changing the rhythm so that when it’s played normally it’s easy!

Replace

‘Replace’: once the passage is being played more confidently, suggest that your child to goes back a few bars and puts back the ‘repaired’ bars into the piece. With any luck, the muscle-memory should do its thing and the fluency will have been improved. Of course, it might take a few sessions working on the same section, but ten minutes of this very targeted practice will be much more beneficial than a longer stint just playing pieces through.

If your child can get into the habit of using the three ‘Rs’ in their practice, and a practice session becomes really meaningful, the progress from week to week will be noticeable. Of course, it’s important to play pieces through, but practising them the right way is the key to being able to play them fluently and of course, with expression, articulation and musicality.

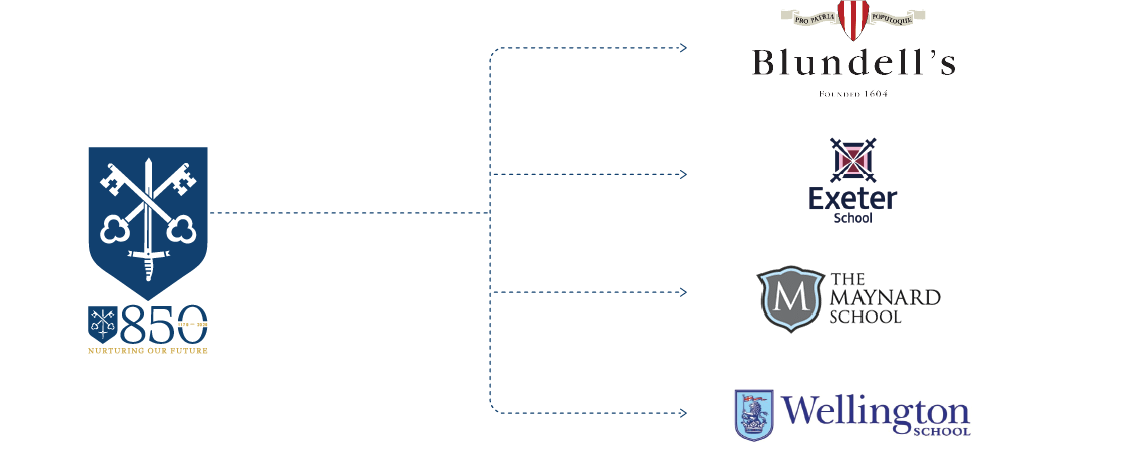

Tonight we hold our Senior Recital Evening, for those pupils who have recently been working towards scholarship auditions at Senior Schools. Between them, working on the basis that they might have practised for a total of 60 minutes a week for the past five years, I calculate that they have clocked up a whopping one thousand, five hundred and sixty hours of practice between them, and, judging by the standard at which they are now playing, it’s been time well-spent. Whilst they’re not quite at the 10,000 hours mark yet, it’s proof that proper practice makes for polished performances.

*With my juggling aspirations in mind, I asked Mrs Stallard to tell me how long it would take to rack up 10,000 hours of practice if I juggled for 30 minutes, 3 times a week and her answer was “127 Years 44 Weeks 3 days and 16 hours (assuming there are no leap years!)”. I reckon I’ll stick to music.

Mrs Julia Featherstone

Director of Music